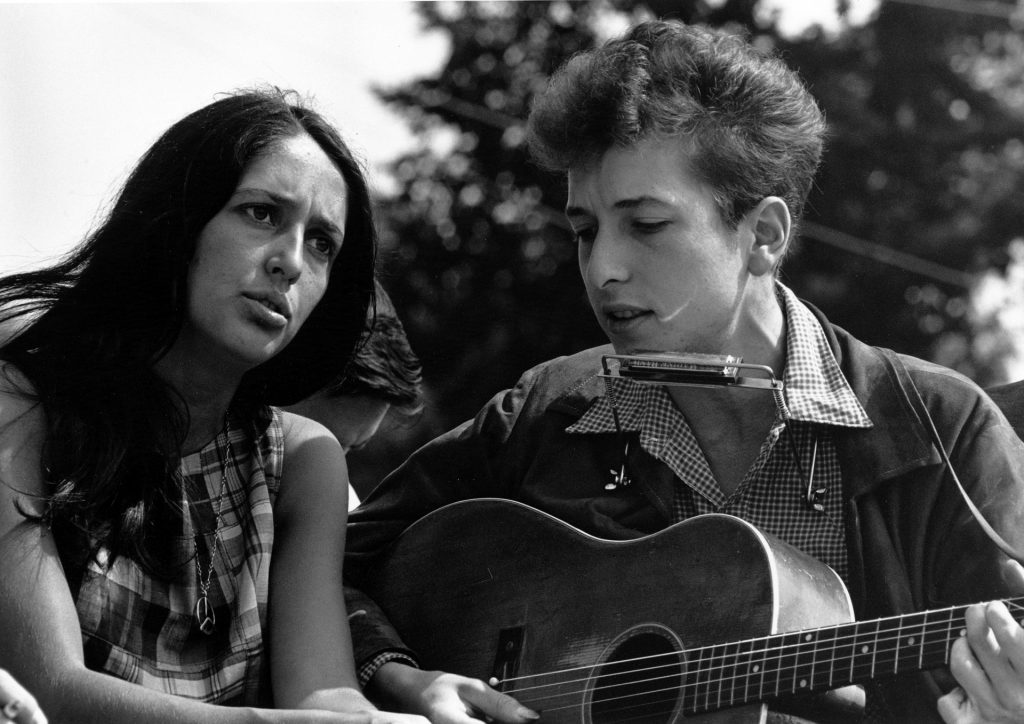

Bob Dylan sang those immortal words in 1964. Indeed, it sure seemed that way. That year the Civil Rights Act was passed outlawing discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. It was a turning point signifying a shift in a nation’s values. But values don’t change overnight. And while the Civil Rights Act was a landmark civil rights and labor law, the evolution of our values is still happening.

The slow progression of change is not unique to this issue. It is applicable to any value held by the collective. Social values are the broad cognitive foundation upon which people’s prioritizations are built. If you value something, you prioritize it. I value my dog. Which means I regularly say no to social engagements and rearrange my schedule in order to spend more time with my four-legged, nonverbal, short-lived pet. I value her over most people.

What does my over attachment and debatably misplaced value of my dog have to do with deer? Well, a lot. Social values define how we prioritize wildlife too. A large and incredibly insightful study was just completed looking at America’s Wildlife Values: the social context of wildlife management in the U.S.

“The purpose of the America’s Wildlife Values Project was to assess the social context of wildlife management in the U.S. to understand the growing conflict around wildlife management. It is the first study of its kind to describe how U.S. residents within and across all 50 states think about wildlife, and how changing perspectives shape the wildlife profession.”

Disagreements regarding wildlife management are rarely the result of biology. Conflict is almost always driven by differences in values among stakeholders. Knowing the wildlife values of constituents can predict their position across a range of issues from endangered species to predator control.

Since people like fitting things into neat little boxes, there are 4 categories to which wildlife values can be assigned:

- Traditionalists (or Utilitarians) – believe wildlife should be used and managed for human benefit

- Mutualists – believe wildlife are part of our social network and that we should live in harmony

- Pluralists – prioritize these values differently depending on the specific context

- Distanced – often believe that wildlife-related issues are less salient to them

So what does the wildlife value landscape look like today in the U.S.?

Traditionalists account for 28% of the population, Mutualists 35%, Pluralists 21%, and Distanced 15%. A similar survey was conducted in the western U.S. in 2004. Comparison in those states shows on average a 5.7% decrease in Traditionalists and a 4.7% increase in Mutualists.

Wildlife values are strongly tied to other aspects of society and life like race, urbanization, education, and income at the state level.

Notable findings:

- Whites had a higher proportion of Traditionalists than all other groups and much lower percentage of Distanced. Hispanics and Asians had the largest proportions of Mutualists. Native Americans had the largest proportion of Pluralists.

- Modernization is driving change in wildlife values. States with higher proportions of people with a Bachelor’s degree, with incomes above the national mode, and living in mid- or large-sized cities have higher proportions of Mutualists and lower proportions of Traditionalists.

Pennsylvania is not too far off the national average with 30% Traditionalists, 33% Mutualists, 24% Pluralists, and 13% Distanced.

But the times, they are a changin’. Millennials are the largest adult generation in the U.S. They are more educated and more racially and ethnically diverse than previous generations. Ethnic and racial minorities are a growing proportion of the population making up 30% of the voting public by 2020 (compared to 21% in 2000). And income is rising.

What does all that mean for wildlife values?

Armed with the information in this survey, we can expect to see the mutualist view point grow while the traditionalist view fade. State wildlife agencies need to recognize and adapt to this reality. While legal hunting is approved by 80% of Americans, this may not remain the norm if its value and purpose is not communicated to society as hunting approval is correlated with being male, white, and living in a rural area. Lower approval of hunting is associated with being female, Hispanic, black, and living in an urban area.

Regardless of how wildlife values are classified, the most important thing is that wildlife IS valued. This is good news. Because people are willing to support and pay for what they value. Most state wildlife agencies are funded by directly through license sales or indirectly through taxes of related equipment. Nationwide, almost 35% of all wildlife agency funds came from license sales. Another 30% comes from federal funds resulting from the Pittman-Robertson Act.

It doesn’t seem quite fair that less than 10% of the US population (hunters and anglers) shoulder the majority of the financial burden of wildlife management, and given the steady decline in those participating in these activities, those funds are shrinking. However, in Pennsylvania, 72% of people support future funding of fish and wildlife management through license fees and public taxes. Indeed, 75% think that’s how we are funded now.

Studies like the Deer-Forest Study which seek to expand our knowledge of proper stewardship of deer and the habitat on which they and other species depend will likely be supported as mutualist values increase as they favor environmental protection over economic growth. In Pennsylvania, both hunter and non-hunters (59% and 67% respectively) agreed that society should strive for this.

There is a lot to think about. We often move in circles that insulate us from the changing world. Everybody wants progress, but no one likes change. But you can’t have one without the other. Remember disagreements about wildlife management are rarely based on biology. So we better start figuring out how society values wildlife and act accordingly. Because as that Noble Prize-winning poet sings “you better start swimmin’ or you’ll sink like a stone, for the times they are a-changin’.”

Wildlife Biologist

If you would like to receive email alerts of new blog posts, subscribe here.

And Follow us on Twitter @WTDresearch