It’s February. We are deep in the cave of winter. Worn down, cold, tired, dreaming of spring.

But not this year! As I type, it’s 54 degrees outside. Crazy! Since winter has taken a hiatus, many species are moving into spring activities. I’ve heard peepers, seen robins are in the yard, and I am thinking about antlers.

I like to remind everyone that I have no interest in antlers or whose head they are attached to. However, when they become detached from that head, it’s a different story. I like to shed hunt. Heaven in my book is a warm March day with my dog and my muck boots traversing fields, rabbit patches, and oak stands surrounded by peepers and bird song. It only gets better if I find what I am looking for.

I say March day because that is usually when the weather breaks, not because that’s when antlers are on the ground. There are surely antlers waiting to be found in January but who wants to be outside then? Not to mention the snow that keeps secrets buried beneath.

Even when the snow is gone finding an antler can be akin to finding a needle in a haystack. There are a lot of sticks in the woods. Shocking I know. Your eye and brain must be trained to see an antler among the littered forest floor.

Can your eyes and brain be trained to see one specific thing?

Being a biologist, I am familiar with the term search image which (according to The Economy of Nature textbook I have on my shelf) is defined as a behavioral selection mechanism that enables predators to increase searching efficiency for prey. Surprisingly, the role of behavior was neglected in early 20th century studies of evolution and ecology. Not anymore! Foraging behavior dominates behavioral ecology research.

The study of foraging behavior spawned theories like optimal foraging – a set of rules by which organisms maximize food intake per unit of time or minimize the time needed to meet their food requirements.

Why would an animal need to maximize food intake/unit? Or be efficient when finding food? Really, squirrels have nothing else to do but look for food all day.

There is more to being a squirrel or deer or fox or bear or skunk or bobcat than just looking for food. A big one is survival, the other is reproduction. And evolution favors those that maximize the benefits (food intake) and minimize the costs (energy expenditure), e.g. optimal foraging.

If you’re a prey species, you must forage efficiently to minimize your chance of being killed. If you’re a predator, you must forage efficiently to minimize your chance of starving to death. Evolution does not favor those who die regardless of cause.

There are reams of research on foraging behavior and optimal foraging theory. Models developed, predictions tested, assumptions made. In the animal world, there are generalist and specialists. Specialists usually have morphological or behavioral adaptations that are highly specific to their food making them extremely efficient at foraging. Pandas are a classic example of a specialist. Generalists are not highly efficient at securing one type of food. Instead, they have foraging options if a preferred food becomes scarce or unavailable. A key to efficiency for both specialists and generalists is the development of a search image.

While generalists have several food options available to them, they don’t just go around willy-nilly looking for food on their grocery list. They often focus on one item when it is abundant to the exclusion of other foods. Developing a search image helps the animal focus and forage more efficiently. If a food item becomes less available, a generalist can recondition its response by learning a new search image. Cool stuff.

Blue jays, quail, and even people have been shown to develop search images. Which brings me back to those antlers. To more efficiently find an antler, I need to develop a search image for it. Efficiency in this case is simply finding one at all.

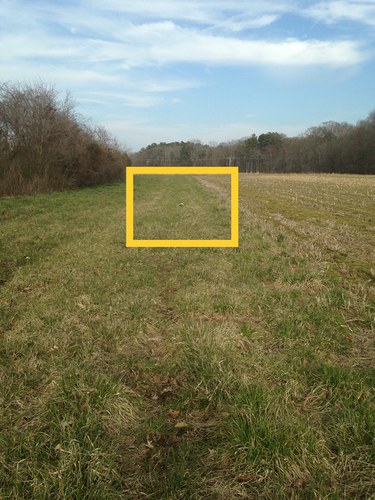

Take a look at the lead photo. See anything?

Two years ago on a warm March day, I went for a walk with my trusty sidekick. Glancing at the field, something caught my eye. Taking 3 strides off the road, my predator brain knew exactly what it was. I rushed to pick up my large prize!

I was pretty excited. Hence the photo documentation of the event.

While my quarry is antlers, there are many worthy prey items. Beaches can overwhelm any human predator if their search image is not defined. Knobbed whelks, lightning whelks, channeled whelks, lettered olives, augers, nutmegs, scallops, mud snails – all dancing about on the sand. Try finding a shark tooth without a search image.

Obviously, some are better searchers than others. This is some of Duane’s haul over a 3-year period.

Thankfully, these are not life or death circumstances. But some research depends on it. Like finding scat. Deer scat is collected as part of the Deer-Forest Study for DNA typing. Crews need to learn what brown deer poop looks like among brown leaves and black mud.

Our ability to form search images and learn new ones speaks to how important this skill was and is to our evolution. Now off to refine and reinforce that search image!

Jeannine Fleegle

Wildlife Biologist

PGC Deer and Elk Section

If you would like to receive email alerts of new blog posts, subscribe here.

And Follow us on Twitter @WTDresearch