Pennsylvania is home to two cervids – elk and white-tailed deer (of course). But on rare occasions, a third makes an appearance.

I am not referring to Alces alces, the largest and heaviest member of the deer family whose species range falls well short of Pennsylvania. But instead to Odocoileus virginianus bullwinklus.

Ok, there isn’t a new species of deer in Pennsylvania or anywhere else. But when your nose swells to the size of a moose, it seems appropriate. Whispers about Bullwinkle syndrome began at the turn of the last century. Since then, there have been 27 reported cases in 14 states including Pennsylvania.

There is nothing that gets wildlife veterinarians and some biologists (like me!) more excited than critters with new or uncommon potential disease syndromes. Recently, a group of these cool and smart people published the case series on this aptly named phenomenon.

When you find something weird or unusual, the first thing you should do is take a few pictures and describe what you see. This is a good life rule. Bullwinkle syndrome is characterized by swelling at the end of the muzzle and upper lip. The lower lip does not appear to be affected in most cases.

Once the outside is properly documented, it’s time to CUT IT OPEN! That is the most fun and best part of the whole process. And this, of course, is exactly what the smart people did. Inside, “the swelling was isolated to the subcutis, underlying muscles and other soft tissues. There was typically no significant thickening of the epidermis, and alopecia was not evident or was minimal.” Translation, swelling was only in the soft tissues under the skin; the skin was not affected; and there was no hair loss on the nose.

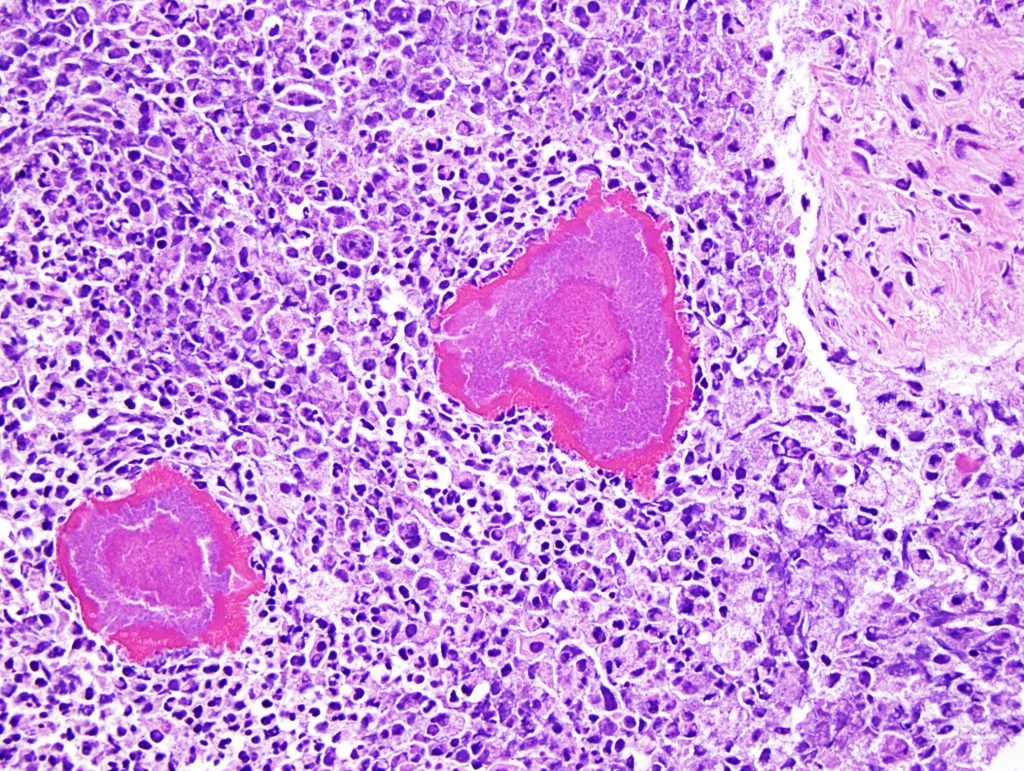

After gross examination, which is needed to rule out any sort of physical cause, like trauma, they broke out the microscopes. What they found were granulomas associated with multifocal inflammatory infiltrates, fibrous connective tissue, macrophages, neutrophils, and Splendore-Hoeppli material. Granulomas are small areas of chronic inflammation and were found through the affected tissue. Beyond that don’t ask me to explain. I told you these were smart people.

Within the Spledore-Hoeppli material, they did find colonies of small rod-shaped bacteria. They were seen in all 27 cases and were consistently gram-negative. Petri parties were setup to try to culture this bacterium. But they didn’t find just one species. Lots of fun cellular critters grew like Trueperella pyogenes and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Nineteen different species in all. This is normal because chronic inflammation usually gets all sorts of secondary bacteria associated with it. But those bugs didn’t throw the party. They just showed up to it. Of the 19 party goers, none had the characteristics of the gram-negative bacteria seen in the granulomas. So who was this mystery microbe?!

Time to break out the BIG, or I should say the little, guns – laser-capture microdissection and DNA amplification. Oh yeah! With this technique, researchers can specifically remove the part of the granuloma with the mystery microbe and then sequence its genes without being distracted by the other party goers.

Mannheimia granulomatis was found in 7 of 8 deer for which samples were available. Score! There have been no previous reports of granulomatous (inflammation) disease in deer caused by this bacterium. Although it has been documented to cause disease in cows in South America called lechiguana.

Not being a moose, this type of nose job looks awful on and for the deer. However, no mortality has been attributed to this condition. In fact, one deer had been seen for 3 years before it was collected. But mortality isn’t the only concern surrounding wildlife disease – why are we seeing this now? Why is the nose only affected? How are animals infected? What makes an animal susceptible?

These are not new questions and hover around all novel wildlife disease outbreaks. Understanding them can give us insights into changing environments, emerging threats to both wildlife and people, and advance techniques for studying disease.

If you see a deer sporting a Bullwinkles schnoz (or other out of the ordinary appendage) on your trail camera or in the woods, drop your wildlife agency a line. Because we aren’t in Moosylvania.

–Jeannine Fleegle

Wildlife Biologist

PGC Deer and Elk Section

Featured Image by Manfred Richter from Pixabay